In my interviews with Filipino bloggers , I would always ask them, “Who is your audience?” They’d often answer, “Oh, I really just write for myself.” I had difficulty understanding this, because if you’re writing for yourself, why bother putting your thoughts online in the first place?

Sarapen is my research blog. I set it up to communicate with the Filipino bloggers I was studying. However, it’s moved away from that ideal. There aren’t as many Filipino bloggers reading me as I expected. This is partly because I haven’t participated in the extended blogging conversations necessary to be drawn into a blogging community. I don’t have the time, and since my data collection is already done, there’s really no point, and it would just be extra work for me.

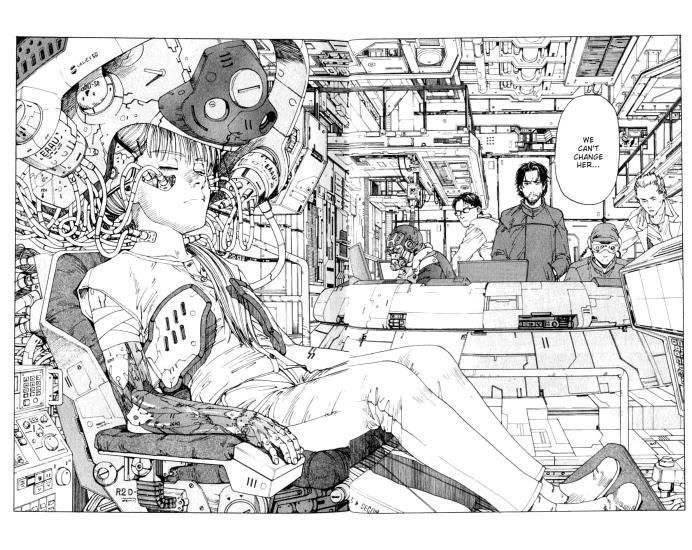

And as you may have noticed, this blog is becoming more and more self-indulgent. My titles have continued to be enigmatic, with the in-jokes largely apprehended by only myself. Or look at the subjects of my preceding posts: Zapatismo, anarchism, Japanese comics, free journals, and a short description of what I was watching on tv. Only two of the last ten posts have been on topic, and I’ve even set up Tangents as a new category to classify posts under (incidentally, I’ve just realized that as a classifier I’m a lumper and not a splitter). In other words, Sarapen is rapidly becoming about me instead of my research.

I’d like to think that the tangents I go on aren’t just intellectual “self-abuse,” as the Victorian British put it (that “it” being masturbation). Rather, my wanderings help me stay on track with my research by keeping my brain a lean, mean, analytical machine. Not only that, I get to think of something besides identity construction, which I think too much about these days. Regardless of that, though, Sarapen is no longer a tool for disseminating information on my research so much as a device for keeping my mind from getting tired.

So now I think I understand what my participants meant when they said they were writing for themselves. Frankly, I thought blogging would just be a necessary chore, but I really honestly have learned more about bloggers by jumping on the bandwagon. Instead of an intellectual appreciation of blogging, I have an embodied understanding of it. I compulsively check my blog statistics, I compose blog posts in my head when I find something sponge-worthy, I gleefully examine the map of my readers’ locations. I get it. Kind of.

Still, the idea of blogging for yourself reminded me of what Mikhail Bakhtin wrote about how dialogue works. As Bakhtin says, dialogue is only possible because the speaker not only addresses the other person specifically, but also keeps in mind that what he or she utters can be understood by a perfect audience, the superaddressee. Which is to say that misunderstandings can occur in any dialogue, but a speaker will attempt dialogue anyway so long as he or she believes that what was said can be understood perfectly by someone (whether that audience is God, history, reasonable people, or so on). So what if, in this particular kind of blog speech, the superaddressee is the self? The perfect audience who will understand perfectly what the blogger wrote is the blogger’s own self, whereas the specific audience consists of anonymous or not-so-anonymous others. Blog dialogue as semi-monologue, then?

The problem is that I only know enough about Bakhtin to be dangerous to myself. I can’t tell if what I’ve proposed really hangs together, especially since this stuff is tangential to what I’m actually working on. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, I always knew being weak in linguistics would come back to bite me in the ass. People in sociocultural anthropology should really be more familiar with linguistics, especially linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics. But now I share it for posterity’s sake and in hopes that someone might tell me if I’ve embarrassed myself or not.

PS

Happy Turkey Day, Canada.