It’s amazing how having constant high-speed Internet and cable tv means that one no longer has to go out as much. I’ve been doing my best to get caught up on watching cartoons, reading comics, and generally lounging about in sybaritic fashion. For instance, I spent last Sunday afternoon eating grapes and watching the dvd boxed set of Season 1 of Carnivale.

It’s wonderful to waste free time. And yet, time is not wasted when one’s mind is productive. Even when I’m not thinking about my thesis, I’m thinking about my thesis, and connections spring up during my relaxation in many delightfully surprising ways.

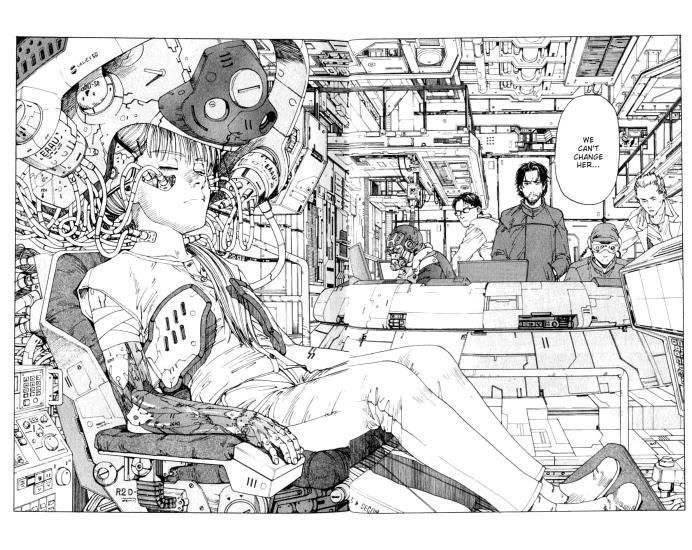

In this case, I’m talking about Eden, another Japanese comic book series (also known as manga) that I’ve recently come to like (thank you MangaProject). It’s about a young man living in a world where a pandemic has brought the world to the brink of disaster, and where a new world order has sprung up as a result. I have to tell you, in the following discussion of Eden I’m going to dispense spoilers like crazy. So read on at your own risk. There’s too much stuff to cover in one post so I’ll revisit the series again later. If you want my thoughts on Eden in a nutshell: Cyberpunk, biopolitics, near-apocalypse — rock! Read it if you need something to flip through when you want to pretend to yourself that you’re working.

Anyway, the new disease is called the Closure Virus, which has killed 15% of the world’s population decades before most of the story’s action takes place. Bear in mind that 15% may not sound like a lot, but that’s still hundreds of millions of people dead, not to mention the many more that are implied to have died from the chaos that erupted. Governments collapse and a new organization exploits the power vacuum to put itself in charge — the Propater.

In the book, Propater is a neoliberal theocracy of federated nation-states controlling what we would call the “West” plus most of the Americas. I know, “Propater” sounds made-up. The name actually comes from Gnosticism, a religious movement from the same era as early Christianity. In fact, if you’ve got some knowledge of the Gnostics and of early Christian theology then you’ll be able to appreciate better some of the references in the series. I feel embarrassed I hadn’t caught on to the Gnostic elements until I’d read the series glossary, where it was all spelled out. Gnosia and agnosia, the aeons, God as insane: these are all things that are mentioned in the book, and they’re all important in some way to the story and its themes. Actually, googling around reveals that the major characters are named after Gnostic deities and they all play similar roles in the story as in Gnosticism.

The Catholic Encyclopedia (take that Wikipedia) says this about Gnosticism:

The doctrine of salvation by knowledge. This definition, based on the etymology of the word (gnosis “knowledge”, gnostikos, “good at knowing”), is correct as far as it goes, but it gives only one, though perhaps the predominant, characteristic of Gnostic systems of thought . . . Gnostics were “people who knew”, and their knowledge at once constituted them a superior class of beings, whose present and future status was essentially different from that of those who, for whatever reason, did not know. A more complete and historical definition of Gnosticism would be:

A collective name for a large number of greatly-varying and pantheistic–idealistic sects, which flourished from some time before the Christian Era down to the fifth century, and which, while borrowing the phraseology and some of the tenets of the chief religions of the day, and especially of Christianity, held matter to be a deterioration of spirit, and the whole universe a depravation of the Deity, and taught the ultimate end of all being to be the overcoming of the grossness of matter and the return to the Parent-Spirit, which return they held to be inaugurated and facilitated by the appearance of some God-sent Saviour.

However unsatisfactory this definition may be, the obscurity, multiplicity, and wild confusion of Gnostic systems will hardly allow of another. Many scholars, moreover, would hold that every attempt to give a generic description of Gnostic sects is labour lost.

Oh, and apparently Christian Gnostics were responsible for early Christian fanfiction:

The Gnostics developed an astounding literary activity, which produced a quantity of writings far surpassing contemporary output of Catholic literature. They were most prolific in the sphere of fiction, as it is safe to say that three-fourths of the early Christians romances about Christ and His disciples emanated from Gnostic circles.

Setting aside the fact that this version of the Catholic Encyclopedia is rather old and it’s often amusing to read the snide jabs at other religions, it’s interesting that anyone would structure a manga around Gnosticism. However, Eden isn’t the only manga or anime to take its inspiration from Christianity and related religions. I’ve never read the manga or watched the anime, but I know Neon Genesis Evangelion also explicitly explored themes from Christianity and Kabbalistic Judaism, though its treatment of such was apparently problematic. I did watch two episodes of Ninja Resurrection, a godawful anime miniseries about rebellious Christians in feudal Japan and the rise of the Anti-Christ or something.

Anyway, I think it’s fair to say that there’s a widespread fascination with Christianity in Japan, perhaps analogous to the fascination with Buddhism in the reified West. Perhaps this fascination comes from a desire for authenticity, with that authenticity being searched for in the foreign. So foreign = Other, Other = authentic, and conversely, domestic = Same, Same = inauthentic. This BBC article on one manifestation of Christianity in Japan presents an interesting but somewhat exoticizing view on the topic.

However, it’s debatable just how alien Christianity really is to Japan. It’s been in the country for 450 years, meaning that Christianity in Japan is almost as old as it is in South America. Christians have played major roles in Japanese history, perhaps most famously in the rebellion of Amakusa Shiro (depicted in Ninja Resurrection), not to mention the extensive meddling in feudal Japanese politics that Catholic missionaries engaged in. And as the BBC article shows, certain Christian sects are quite popular in modern Japan. So just how Other is Christianity really?

Oh whatever, I’m hungry and my rice just finished cooking. I’m definitely coming back to Eden, but see you some other time.