So, herewith is a recap of my summer (and now fall) reading history.

The first book I’m discussing is Too Dumb for Democracy? Why We Make Bad Political Decisions and How We Can Make Better Ones by David Moscrop, a Canadian former political scientist and current op-ed columnist. It’s about the psychological short hand that people in Western democracies use to vote and the tricks that political parties and governments use to try to guide those same voters to preferred outcomes. The book is actually quite easy to read and replete with personal anecdotes and examples from psychological studies to demonstrate the principles being talked about, as well real world examples drawn from US, British, and Canadian politics. However, I can tell that I actually know more than the author about the psychological side of things (or he’s content to keep things at an introductory level for his audience), whereas I’m also something of a news junkie and a poli sci nerd and so am already familiar with what he’s talking about on that end. So the book is a good introduction on these topics but not really something I personally found educational.

The second book is one I really enjoyed reading, which is Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott. Scott is also a political scientist, but in addition he trained in anthropology and specializes in comparative politics, especially with regard to peasants and agriculture. The book itself is about the historical transition from hunting and gathering to state societies, as well as the people who refused to join the state (a.k.a. the barbarians). The whole thing is completely my jam. Scott is an anarchist, so he’s of course got a low opinion of the state, but his description of how human misery increased once people took up agriculture is old news among anthropology circles (and probably familiar to anyone who read Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel).

However, Scott goes quite a lot into the comparative details and argues that the state is inherently an unstable formation that requires incredible amounts of resources to keep going, but which is also doomed to fail thanks to the unsustainable demands it makes on the environment, the punishing taxes and labour it demands of its people (usually to fund wars to capture more territory where workers live which in turn demands more wars to capture even more workers in an endless race) which drive the citizens to escape into the hinterlands or revolt, and the regular return of lethal epidemics that are cooked up thanks to all the animals that agriculturalists live with and the cities and trade networks of a complex state society that concentrate and spread pathogens. Scott even argues that the collapse of a civilization might be better termed a reconfiguring, since it’s basically the people of a territory reorganizing themselves into a less precarious status quo.

Of course, preying on the states are the infamous barbarians, which Scott points out weren’t necessarily just alien societies robbing from the civilized. In fact, when the workers of historical states – the peasants, serfs, slaves, and everyone else who’s not an elite at the top of the social pyramid – get fed up with forever being drafted into wars and literally breaking their backs working the fields, they always had the option of joining the barbarians. Why bust your ass when you can have someone else do it and then take their stuff? In turn, a state had the option of repelling the barbarians or paying them off, but either way, it was another state expense. So a state inevitably had its barbarian “dark twin” (more than one sometimes) which grew when the state flourished and disappeared when the state did.

But alas for the barbarians, technological progress ended their viability, since you can’t exactly build Maxim guns out on the great plains, otherwise the Navajo might have forced the early US to cough up protection money like for example how the Uyghurs did to the Chinese or the Celts did to the Romans (though the Chinese usually called this tribute “gifts” and pretended that it was all from the emperor’s munificence).

Anyway, my one criticism of this book is that it just abruptly ends. It goes into the barbarian thing and then that’s it, no closing chapter, no summary, no discussion of the argument that was presented. But otherwise I’d say this is my favourite book of 2021.

Finally, the last book I’m covering is actually the first three books of the Giants series by James P. Hogan: Inherit the Stars, The Gentle Giants of Ganymede, and Giants’ Star. I actually read the manga adaptation first and wanted to know how the original compared. Well, you can tell that these books were written in the 1970s because of the incredible amount of sexual harassment in them. I’ve read lots of Asimov and Heinlein and others of that generation – who all came before Hogan – and I don’t remember these other authors having this much sexual harassment in their works. I wasn’t tracking it, but I think every female character in the story is sexually harassed at least once, whether it’s the gals in the stenography pool being seduced by the married physicist, or the telephone operator being pestered for a date, or the secretary whose incredible ass the protagonist admires as she bends forward to look at a computer monitor.

There’s also a lot of smoking and drinking, which especially stood out in the scene where the protagonists are smoking some after-dinner cigars on a spaceship with presumably limited supplies of oxygen (and this is set in the near-future, not some Star Trek utopia with limitless energy and whatnot). So yeah, it feels very Mad Men. But whatever, I remember when smoking indoors was a thing, I can get past that. It really is the sexual harassment that’s the most notable thing about this series to me.

The story itself is about a mummified astronaut being discovered on the moon, the scientists investigating this mystery, and the interplanetary journey to find the truth behind all of the secrets hidden in the past. Anyway, the books are clearly from a certain old school style of science fiction writing because the characters have barely any personality and mostly just jabber about science at each other. Which is mainly why I kept reading, because sometimes I just want to read about nerds arguing over theories of human evolution.

But this paper-thin characterization explains the sexual harassment, which quite frankly feels jarring when it’s inserted into the story, because it’s a clumsy attempt to humanize the male characters. Yes, this was how Hogan thought he could bring his characters to life: by giving his readers something they could relate to. Obviously, he took it for granted that his readers were all men.

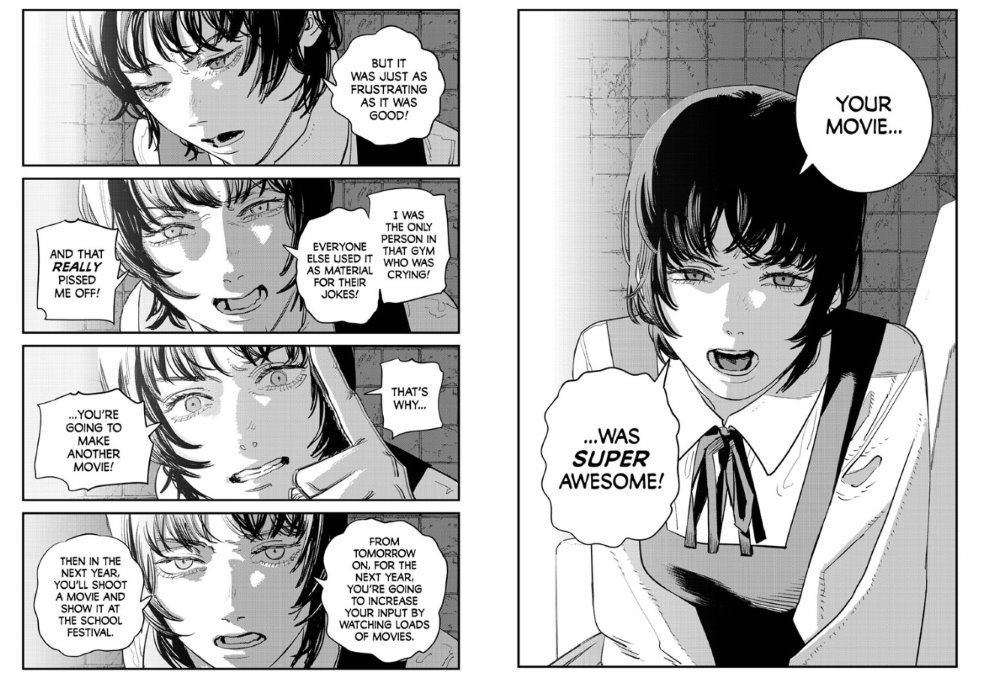

I did appreciate how much better the 2011 Yukinobu Hoshino manga adaptation was, not least for removing the sexual harassment, but also adding the worthwhile female and non-white characters into the story that a white British engineer from the 70s would never have done. It even fixed up some of the science stuff that the original books messed up and moved stuff around so the plot was more engaging.

So yeah, the Giants series. That was a thing.